"You Sank My Aircraft Carrier!" Did a Japanese War Game Predict Defeat at the Battle of Midway?

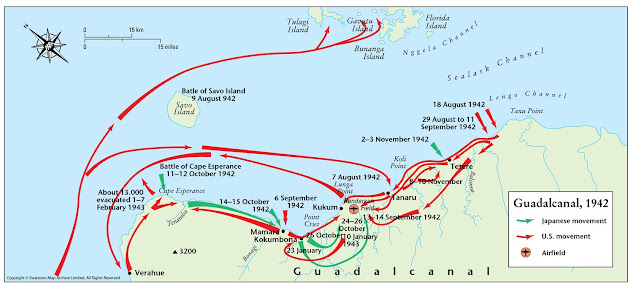

As we prepare to take on the National Naval Aviation Museum in our Battle of Midway war game challenge, it is worthwhile to review the historical events that preceded Midway and examine the role played by war gaming. Japanese planning for Operation MI, the codename for the Midway campaign, began in February 1942. Historians including Craig Symonds, Jonathan Parshall, and Anthony Tully have noted that by the spring of 1942, the Imperial General Staff had become overconfident in the abilities of the Japanese military. Continued success over the first months of the war had expanded Japan's defensive perimeter to encompass the Marshall and Gilbert Island groups as well as a portion of the Solomons. Even when battles were inconclusive, such as the recent engagement in the Coral Sea, the damage inflicted upon U.S. naval forces was significant. Many of Japan's senior commanders believed that Americans simply lacked fighting spirit and could not match the tenacity of Japanese sailors and airmen.

One of the events historians have pointed to as evidence of the Imperial General Staff's superiority complex is the war game held aboard the battleship Yamato from May 1-4. Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku hosted this tabletop exercise and invited all of the senior commanders involved in Operation MI to participate. His chief of staff, Rear Admiral Ugaki Matome, ran the game and served as the chief umpire. In theory, the purpose of the exercise was to fight out the battle on paper first and expose any flaws in the Japanese plan so they could be corrected before launching the actual operation. This game, however, seems to have been treated as a formality rather than a serious tool for improving operational plans. In their book Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway, authors Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully described the game as "four days of scripted silliness" and "a mockery of professional staff work."

One incident during the game that proved especially notorious occurred soon after the Japanese carrier force, known as the Kido Butai, was spotted. The player controlling the U.S. forces (whose name is lost to history) sent a flight of land-based bombers from Midway to attack the carriers. The game umpire rolled a pair of dice to determine how many hits were scored. The result of nine was enough to sink two carriers, Akagi and Kaga. To Admiral Ugaki's mind, however, that was ludicrous. He did not believe the Americans would be so aggressive. Even if they were, he was confident the Japanese carriers would be up to the task of defending themselves. He overruled the umpire and reduced the result to just three hits, meaning that Akagi was still afloat. The destruction of Kaga stood for now, but even it reappeared in a later game covering the subsequent operation planned for New Caledonia and the Fiji Islands.

At first glance, Ugaki's decision appears to be a perfect example of a senior officer insisting that a plan will work while ignoring all evidence to the contrary. After all, American aircraft did indeed catch the Kido Butai by surprise and destroyed Kaga, Akagi, and Soryu on the first day of the battle. Had Ugaki accepted the game results and taken its lessons to heart, he might have taken the American air threat more seriously and acted accordingly.

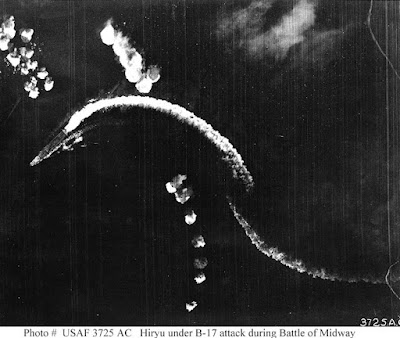

In Ugaki's defense, there was at least one good reason for him to overrule the umpire. The attack in the game was carried out by land-based bombers flying from Midway. In the real battle, B-17s based at Midway found the Kido Butai and dropped dozens of 600-pound bombs on the carriers, almost exactly as the game predicted they would. But contrary to what occurred in the artificial game environment, their results were abysmal. Not a single Japanese ship was hit. Much to the chagrin of the Army's airpower advocates, high altitude bombers simply lacked the technology to hit a warship maneuvering at high speed. Dive bombing and torpedo attacks proved to be the only effective means of sinking a capital ship in the age of unguided munitions. Considering their poor performance, it does not seem unreasonable for Ugaki to have concluded that the bombers in the game had achieved a highly unlikely result that was best overturned.

When considering historical anecdotes like this one, it is always necessary to consider the source. How do we know what transpired in the game? If any records were kept, they did not survive the war. We have no photos of the game being played, and it is almost certain that none were taken. Our understanding of this event is informed by just one eyewitness who took part in the game and lived to write about it many years later. Fuchida Mitsuo is best known as the pilot who led the attack on Pearl Harbor. In May 1942, he was serving as the commander of Akagi's air group and attended all four days of the game as it unfolded on Yamato. He recalled that few of the participants had had any time to review the plan they were now being asked to rehearse. He also felt that Ugaki's main concern was to ensure that the game results validated the plan.

Except for the staff of the Combined Fleet Headquarters, all those taking part in the war

games were amazed at this formidable program, which seemed to have been dreamed up

with a great deal more imagination than regard for reality. Still more amazing, however,

was the manner in which every operation from the invasion of Midway and the Aleutians

down to the assault on Johnston and Hawaii was carried out in the games without the

slightest difficulty. This was due in no small measure to the highhanded conduct of Rear

Admiral Ugaki, the presiding officer, who frequently intervened to set aside rulings made

by the umpires.

Fuchida escaped several brushes with death and survived the war. After converting to Christianity, he founded the Captain Fuchida Evangelical Association in 1950 and became a Lutheran pastor who traveled across the U.S. talking to audiences about his experiences during the war. He put some of his stories to paper in 1951 when he co-authored a book about the Japanese experience in the Battle of Midway. Written for a Japanese audience disillusioned by war and critical of its wartime leaders, Midway: The Battle that Doomed Japan gives great credit to the U.S. Navy while pointing out the shortcomings of the Japanese high command, including Ugaki.

Since its release, scholars have uncovered several inaccuracies in his version of events. For example, he claimed that once Nagumo became aware of the presence of American carriers at Midway, he ordered his aircraft to be rearmed and prepared to strike. These aircraft were brought up to the flight decks and were just minutes away from launching when the dive bombers from Enterprise and Yorktown[?] appeared overhead to ruin the Kido Butai, according to Fuchida. Subsequent analysis of official records showed that the Japanese aircraft were still in their hangars and were not anywhere near being ready to launch. Fuchida also misrepresented his actions at Pearl Harbor and claimed to be present at the surrender on USS Missouri which was later proven to be false.

Given the known errors he introduced into the historiography of World War II, we should at least pause when considering whether to accept his version of events at face value. No other accounts of this game exist that can corroborate Fuchida's story about Ugaki overruling the results of the bomber attack. Should we consider it as evidence of Japanese overconfidence? There were certainly instances in early 1942 when Japanese planners succumbed to "victory disease," but the Midway wargame did not necessarily reflect that mentality. Even if Ugaki did refuse to accept the outcome that foretold of Japanese disaster as Fuchida claimed he did, his decision was sound given the limits of level bombing at that time.

Rob Doane

Curator

Naval War College Museum

Comments

Post a Comment