Operation Ke: War Gaming the Japanese Withdrawal from Guadalcanal

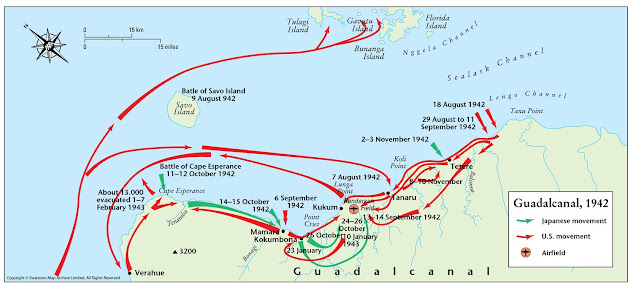

Following American success at Midway, the Joint Chiefs of Staff targeted Rabaul as the first objective in the Allied drive across the southwest Pacific. In order to reach it, a number of outlying Japanese bases needed to be taken first in order to support a major offensive through the Solomon Islands. Initial landings took place on Guadalcanal and Tulagi in August 1942. Tulagi fell after an intense two-day battle, but securing Guadalcanal took seven months even though initial resistance was slight. By December, months of heavy fighting in the jungle and at sea had finally worn down Japan’s ability to contest the island. Japanese soldiers were succumbing to malnutrition and disease at a rate that could not be sustained by the navy’s “Tokyo Express” resupply efforts. The Chiefs of Staff of the Japanese army and navy evaluated the situation and reluctantly concluded they could not hold the island. On the last day of the year, they obtained approval from the emperor to begin evacuating what was left of their ground forces.

Operation Ke was scheduled to begin in late January 1943 using Japanese destroyers as the evacuation force. Allied reconnaissance and radio traffic intercepts revealed that preparations for an operation were underway, but intelligence officials believed the signals pointed to an offensive aimed at retaking Guadalcanal. Believing that the Japanese were mounting a major attack, Admiral Halsey kept his forces at a safe distance to prepare for the coming battle.

On February 1st, 4th, and 7th, the Japanese navy successfully evacuated 10,652 men from the island. Two days later, Major General Alexander Patch of the U.S. Army declared the island free of Japanese forces. The Japanese lost 20,000 soldiers in the Solomons and would remain on the defensive for the rest of the war. By the end of 1943, the Allied advance reached Bougainville, bringing Rabaul under sustained air attack and rendering it useless as a major Japanese base.

Operation Ke could be judged a minor success for the Japanese since they succeeded in saving a division-sized element to fight another day. Halsey held most of his available naval power south of Guadalcanal to shield troop transports from possible enemy offensive operations. Likewise, senior Japanese naval commanders kept their heavier units at a safe distance, committing only destroyers to the evacuation runs.

Rob Doane

Curator, Naval War College Museum

Comments

Post a Comment