Live War Game Demonstration: Pre-Game Briefing Part 2

Like Formosa, U.S. war planners valued the Ryukyus primarily for their capacity to support land-based bombers. The island group also had enough anchorages to function as an assembly depot for the invasion of Japan. The siege strategy originally envisioned in the 1920s and 30s had foreseen the capture of Okinawa as a trigger that would bring about the much sought-after decisive fleet action. As it turned out, the Japanese battle fleet was destroyed at Leyte Gulf five months before Operation ICEBERG commenced. With the exception of the battleship Yamato, Japanese surface forces proved little threat to the invasion. Air power was a different story. Having lost most of its carrier aircraft at the Battle of the Philippine Sea, Japan now turned to kamikaze attacks as a desperate means to resist further Allied advances.

Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, Commander Fifth Fleet, was in overall command of the operation. Vice Admiral Richmond K. Turner oversaw the amphibious phase of the operation. His job was to get Tenth Army ashore as quickly as possible, at which point its commander, Lieutenant General Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr., would begin reporting directly to Spruance. Spruance and Turner were both graduates of the Naval War College and had helped develop the Navy’s amphibious doctrine they were now charged with putting in to practice. In the 1930s, the Marine Corps partnered with the Naval War College to experiment with amphibious operations. NWC students played out beach landings on the war gaming floor in Newport, and the lessons learned from these studies informed the plans for the Fleet Landing Exercises carried out between 1935-1941. Among the many issues the Navy wrestled with was whether aircraft carriers should remain close to the beaches to provide ground support, or cruise on their own to hunt down enemy surface forces. ICEBERG would provide the ultimate proving ground for answering those questions and more.

|

| click to enlarge |

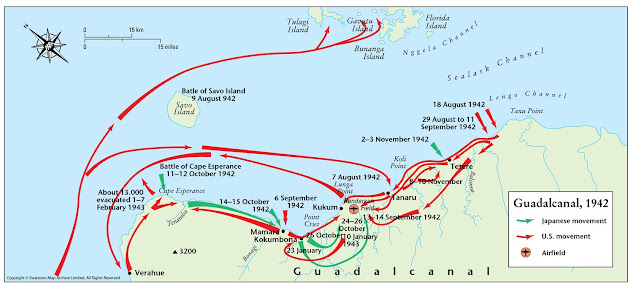

Before the first American soldier could hit the beach, their supplies, fuel, ammunition, food, and equipment had to be transported there. Planners realized early on that logistics for the invasion would be challenging. The decision to bypass Formosa meant that it could not be used as a base for launching the attack. The Navy would have to mount the assault from either the southern Philippines, the Carolines, or the Marianas. The closest base large enough for the task, Ulithi, was 1,370 miles from Okinawa and required five days sailing time. Troops and supplies departed from the U.S. west coast, Oahu, Espiritu Santo, New Caledonia, Guadalcanal, and the Russell Islands, and assembled at Eniwetok, Ulithi, Saipan, and Leyte. The west coast, which furnished the bulk of resupply, was 7,192 miles away and required 26 days sailing time. The vast distances and lengthy transit times required the adoption of a schedule of staggered supply shipments. The task of coordinating these movements and ensuring that soldiers and supplies arrived on time where they were needed was a challenge of staggering proportions.

|

| Japanese anti-tank gun on Sugar Loaf Hill click to enlarge |

Based on experience at Peleliu and Iwo Jima, American intelligence officers expected Japanese forces to defend forward close to the beaches and mount counterattacks to throw the invaders back into the sea. Accurate intelligence was difficult to gather, however. Heavy cloud cover over the island in the winter months prevented accurate photo reconnaissance. Allied aircraft failed to spot the construction of defensive positions on the southern end of the island known as the Shuri Line. Also going unnoticed was the transfer of the Japanese 24th Division from Manchuria to Okinawa. The Navy used submarines to photograph invasion beaches and plot the locations of enemy fighting positions, but such missions were risky even at this late stage of the war. USS Swordfish (SS-193) was lost on January 12, 1945 as it carried out reconnaissance operations off Okinawa. Among its crew was Lieutenant Commander John B. Pye, son of the President of the Naval War College, Vice Admiral William S. Pye.

|

| click to enlarge |

On the morning of April 1, 1945 as hundreds of landing craft headed for the beaches, there was no doubt that Japan was going to lose the war. With its industrial centers destroyed, its access to overseas resources cut off, and its military a hollow shell of the force that went to war with the U.S. in 1941, the only question remaining was how long it would take to bring hostilities to an end. Okinawa was the last major battle of World War II, though nobody knew that at the time. Weeks of intense fighting still lay ahead as Tenth Army, fighting at the end of a supply chain more than 7,000 miles long and facing an enemy who was determined to fight to the last man, prepared to clear the island one hill at a time.

Rob Doane

Curator

Naval War College Museum

Comments

Post a Comment